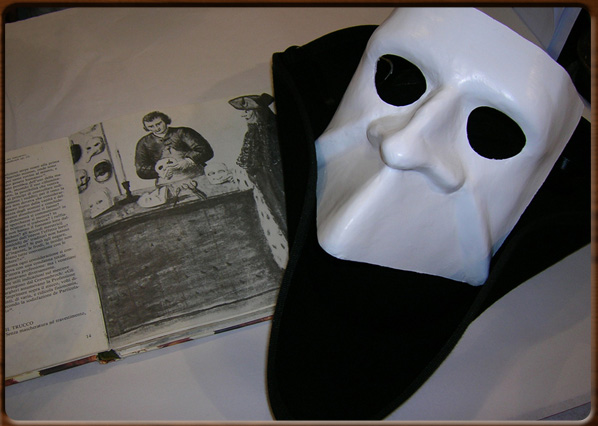

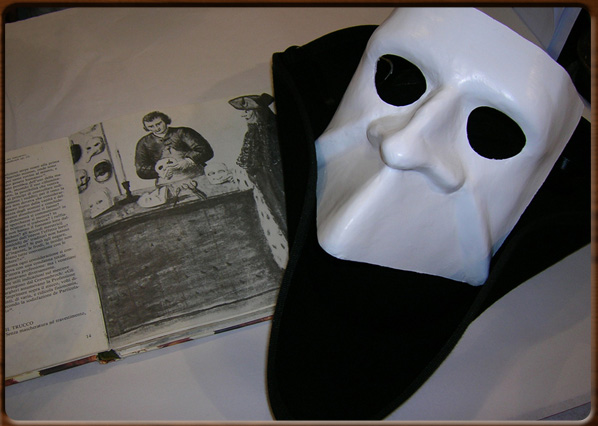

Bauta and tricorn.

Morete.

Harlequin at the theatre.

Punch in love, Tiepolo.

Venetian mask.

Masks in the shop.

Masks of bread.

No video

The “mascareri”

“Mascareri o maschereri” are master craftsmen who still keep alive an ancient and noble profession whose skills were in great demand in Venice in the 1600s and 1700s. The first mention of these craftsmen dates back to 1271, though it was not until April 1436 that the mask makers were granted their own Mariegola under the reign of Francesco Foscari, a copy of which is still kept in the Venice State Archives. Albeit associated with the category of painters, the Arte dei mascareri e de Targheri “targheri” being the makers of face shields was an autonomous corporation until 1620, when it merged with that of the illuminators, designers, gilders and Cartoleri.

Venetian masks craft were – and still are – made using clay models, plaster casts, papier-mâché (with flour glue and gauze) and paint for the final decoration. Records show that in 1773 there were 12 mask workshops in Venice employing 31 people. These always had full order books, considering the almost daily use made of masks by Venetians and foreigners.

In other words, masks were an important commodity and mostly exported.

The rules for wearing masks

The almost daily use of the mask is due to the fact that the Carnevale period lasted a long time in Venice: it began on 26th December and ended on Ceneri, although licences were often granted for the use of masks until since 1st October. Indeed, it was not unusual for parties and mask balls to be held during Lent and the fifteen days of the Festa della Sensa.

In the early 1600s, usage of masks was so abused that on 13 August 1608 the Council of Ten were forced to issue a decree – currently kept in the St. Mark’s Library – that set down rules in order to limit their use. It was prohibited to wear masks during non -carnival periods of the year, in places of worship and during plagues. Masks could only be worn at certain times of the day and without weapons. There was also a ban on wearing masks for prostitutes and men in casinos. “Wearing a mask” also included other forms of disguise, such as fake beards and moustaches, men dressed up as women and vice-versa. There were severe penalties, even two years in prison for men and the public stocks in the case of prostitutes.

The masks in vogue

The Venetian disguise par excellence is the “bauta”, worn by both men and women: a black cape always coupled with a black tricorn hat and a “larva”, a white mask to conceal the face. The bauta guaranteed total anonymity, yet allowed its wearer to eat and drink. It was a mask that made all men (and women) equal during the Carnevale festivities, in theatres and lobbies, during an amorous rendez-vous and any other occasion when one wished to remain incognito.

Another mask, but only used by women, was the moretta o moreta: an oval of black velvet that covered the face and kept in place by a button held between the teeth. The “gnaga” was a very common form of disguise for women and, especially, homosexuals. Other popular disguises were the “mattaccino”, a man dressed up as a child who then went around with others and threw perfumed eggs at beautiful girls, and the “medico della peste”, the disturbing costume worn by doctors during outbreaks of the plague.La Commedia dell'Arte

The most popular masks from the Dark Ages down to the present day are those inspired by the classic figures of the Commedia dell'Arte: the mask was an important recognised part of theatre and several characters became the perfect stereotypes for the Venetian society. The main characters include the mask of Pantaloon, an old rich merchant and hustler; Brighella, a smart servant and the silly Harlequin, both originating in Bergamo; Colombina, a shrewd, gossipy and mischievous servant-girl. Other masks from Lombardy and Veneto included those of Gioppino, Scappino, Traccagnino and Mattaccino. Highly popular “imported” mask from other areas was that of Pulcinella from Naples, the classic lazy buffoon.

1100 - 1200 - - rev. 0.1.8